This is a rush transcript. Copy may not be in its final form.

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org. I’m Amy Goodman, with Nermeen Shaikh.

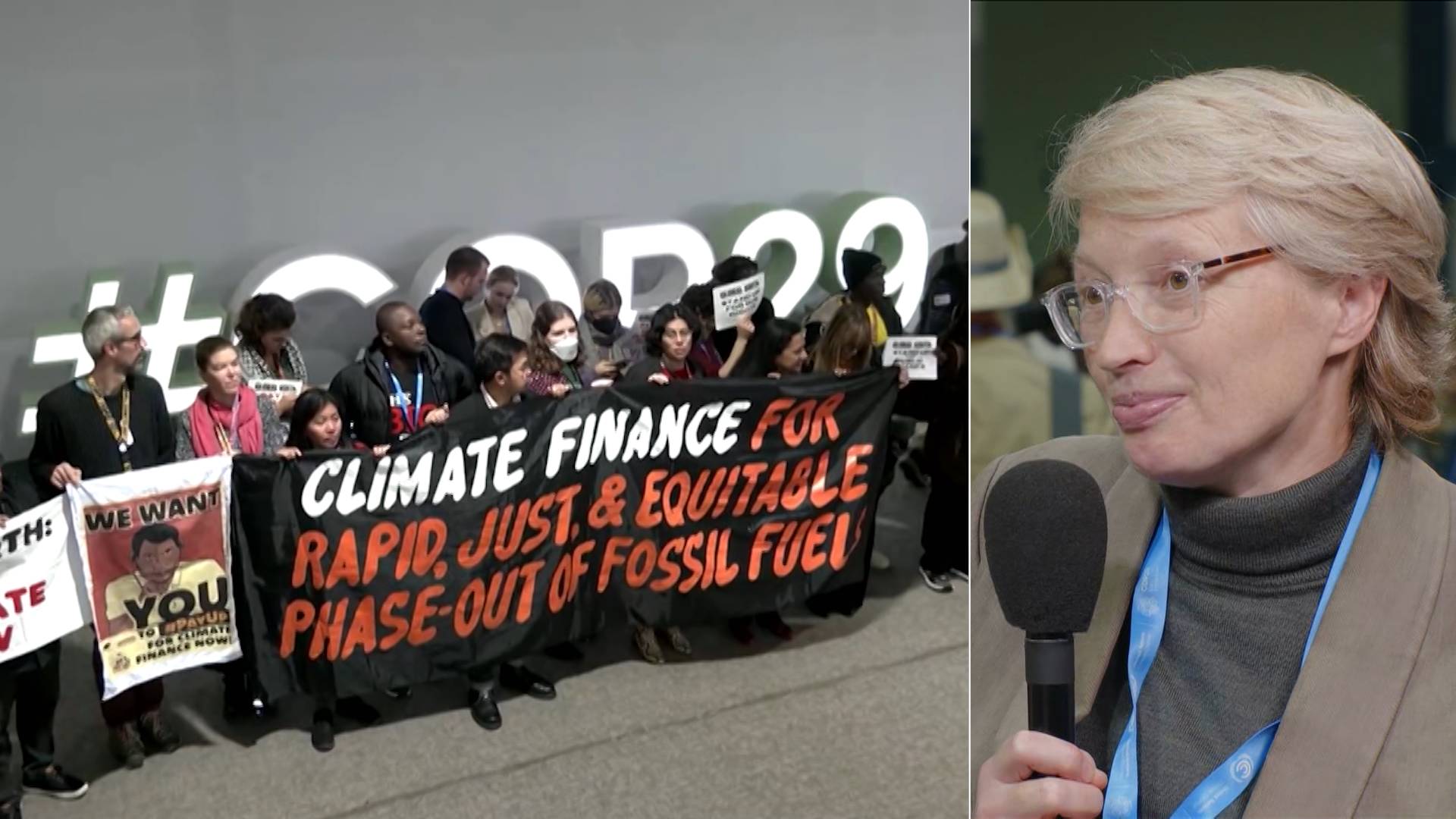

NERMEEN SHAIKH: We’re broadcasting from the U.N. climate summit in Baku, Azerbaijan. In a room behind us, the People’s Plenary is underway, called “Pay Up, Stand Up: Finance Climate Action, Not Genocide,” where civil society just unfurled the names of Palestinians who have been killed, and prayed for the dead.

As the summit is set to wrap Friday for a climate finance deal, a new draft of a possible deal has been submitted and is being condemned by both rich and poor countries. U.N. Secretary-General António Guterres spoke here earlier today.

SECRETARY–GENERAL ANTÓNIO GUTERRES: From now on, what matters is not what was the initial position of each party. What now matters is how to find a compromise that allows for an ambitious result in relation to the new global goal, because finance is in the center of this COP, but at the same time to take into account the concerns of all other countries in relation to the different aspects that are relevant for the future of our battle against climate change.

AMY GOODMAN: That’s the U.N. Secretary-General António Guterres. Among the major issues is the absence of a firm number in the draft text on how much rich countries will pay. Poorer nations bearing the brunt of the climate crisis say at least $1.3 trillion a year is needed.

For more, we’re joined here in Baku by two guests. Harjeet Singh is the global engagement director with the Fossil Fuel Non-Proliferation Treaty. He’s co-founder of Satat Sampada, a social impact organization. He’s based in New Delhi, India. We are also joined by Fiona Harvey. She is the longtime environment editor at The Guardian. And it’s not easy to pin her down for an interview, so we’re thrilled you’re here with us right now.

There is a lot of noise in the background. The People’s Plenary has just gotten out. We hear them talking, although many have put tape over their mouths that say “pay up.” We’ll speak to some of them in a little while.

But, Fiona, it’s really hard to navigate through everything that happens at these U.N. climate summits, maybe partly purposely so people can’t follow. But today the issue is finance. And if you, in lay terms, can break it down for us, what exactly was the statement that was released this morning? What document was released? And what has been the response of the wealthy nations and the poorer nations?

FIONA HARVEY: So, we are here to negotiate a global settlement on climate finance, which is all about getting the funds that the poor world needs in order to cut greenhouse gas emissions, shift to a low-carbon economy and adapt to the impacts of extreme weather driven by the climate crisis. This is incredibly important. This is the — the future of these countries depends on getting this finance.

And what they’re demanding is about a trillion dollars a year. Now, that sounds like a lot of money. It’s actually not a great deal of money when you put it in context. It’s about 1% of the global economy. And it’s really a sum of money that is eminently findable. You know, we already spend — as a world, we spend about $3 trillion a year on energy, about two-thirds of it on clean energy, a third on fossil fuels. So, a trillion dollars a year may sound like a lot, but it’s actually doable.

What’s happened today is that we’ve got a draft text of what should become an agreement to get this money from the rich to the poor. Unfortunately, this draft text is not great. It doesn’t actually have the key numbers in there. And it also — you know, it’s got various kind of clauses and things in there that a lot of people are unhappy with. Now, everyone seems to be unhappy with this text. It’s not just developed or developing countries. It’s pretty much everyone. And it really — I think we need to kind of view it as maybe a first attempt by the presidency, because they’re going to come up with another later today, maybe tomorrow morning, effectively, where hopefully some of these problems are resolved, and hopefully we get some of the key numbers in there.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: And could you explain, even within that, Fiona, the question of finance? How much of that finance, in terms of the negotiations so far, are being considered loans or grants?

FIONA HARVEY: OK. So, if you look at the $1 trillion a year, we need to get — some of that money should come from, directly from, developed countries. But a lot of that money is going to come indirectly in other ways, and some of it will probably need to come from the private sector. Now, that’s controversial for some countries. There are some developing countries who say, “We don’t want the money to come from the private sector.” But, in effect, that’s really going to be necessary to get to the $1 trillion mark, because developed countries who are here are not going to agree to hand over $1 trillion a year among them. That’s not going to happen.

So, what developed countries are likely to agree is probably something like maybe a tripling of the current amount of climate finance, which is $100 billion. So, that could be something like $300 billion a year. And some of that would come directly from developed countries. Some of it would come through multilateral development banks. And then, the rest of the money, some of it would come from the private sector, and some of it could come from new sources of finance, like new taxes on fossil fuels, wealth taxes, taxes on frequent flying and so on. There are lots of potential sources of money out there that really haven’t been tapped yet.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: And could you talk about — because the COP presidency has also come under criticism for not doing enough to make sure that an agreement was reached. And minimally, as you said, the draft agreement that’s been released doesn’t even have a number, much less a good one or a bad one. What role does the COP presidency play in enabling this negotiation and making sure some kind of agreement is reached?

FIONA HARVEY: Well, we are now at a crunch moment. This is the absolute test of this COP presidency. Is this going to be a successful COP or not? It’s in the hands of the presidency now. And so, the presidency has got to take this text, which has been slammed and shot down by pretty much everyone, go away, start again and come up with a text that works. So, hopefully, now what they’re doing is in the back rooms of this conference engaging in shuttle diplomacy, talking to all of the parties, getting their concerns, getting their feelings, and, you know, pushing and being firm with people where necessary.

What they will want to see is a good number from developed countries. What developed countries want to see is also a broadening of the contributor base, because at the moment you have a lot of countries who have big economies and big greenhouse gas emissions, but they don’t contribute to climate finance. So, that’s countries like China, for instance, second-biggest economy in the world, first-biggest emitter by a really long way. And they don’t actually do climate financing the same way that developed countries do. They do do some South-South cooperation, but it’s very hard to judge. So, if China were able to kind of flesh that out a bit more, that might work.

There are also a lot of countries who are making a great deal of money from fossil fuels, and they don’t pay into climate finance — talking about Saudi Arabia here, talking about Qatar and United Arab Emirates. There are countries like that, petrostates effectively, who make their money from selling stuff that creates the problem we’re here to solve.

AMY GOODMAN: Speaking of which, when we’re talking about petrostates, that’s exactly where this U.N. COP, COP29, is taken place. It’s taking place in Baku, Azerbaijan, leading petrostate, the first, I believe, oil-exporting country in the world. And I’m wondering about the significance of this. I mean, outside, civil society, many climate justice activists and journalists have been arrested in the lead-up to the COP who expose oil and gas deals and corruption, leading economists, six journalists with an independent media outlet. And you also have here Global Witness exposing — acting like they were an oil dealer and calling up one of the heads of the — in the COP presidency and saying, “We’d like to make a deal with you.” Before you leave us, Fiona, if you can talk about the significance? Last year, it was in UAE, a petrostate. The head of it was the head of the national oil company. And this year, the repression on the outside and the deals that are being made on the inside — the largest delegation is the delegation of oil lobbyists from around the world.

FIONA HARVEY: It’s a really big issue at COPs. And the role of fossil fuel lobbyists here is terribly problematic. It’s why some very prominent people have been calling here for reform, reform of the COP process so that this can’t happen. They want there to be more control over who’s allowed to be the president of a COP, so that it couldn’t be necessarily an oil state in future, unless that oil state really agrees to actually take action and to agree to phase out fossil fuels and set out a credible pathway towards that. If an oil state were to do that, then I’m sure they’d be welcomed by very many people. So, yes, it’s a problem.

On the other hand, you know, the strength of this COP is that it is global. And every country in the world comes here. Every country is entitled to have an equal say. And that’s really, really important, because it means that the poorest countries can come here and confront the richest countries, who are causing the problem. So, you know, you want to make this COP as open as possible, and to some extent, that means you have to make it open to petrostates, problematic though that it is. So, that’s a problem that everyone here is still wrestling with.

AMY GOODMAN: I guess the question is, if only it was as open to civil society. Fiona, we want to thank you for being with us. We have to take another break, and then we’re going to be joined by a leading Indian climate justice activist. Fiona Harvey, longtime environment editor at The Guardian newspaper. Harjeet Singh will be joining us. As he sits right here, there is a lot happening. The People’s Plenary just opened up, many people gathering around even where we are, and we’re going to talk to some of the activists who just came out of that plenary. Stay with us.

Post comments (0)