This is a rush transcript. Copy may not be in its final form.

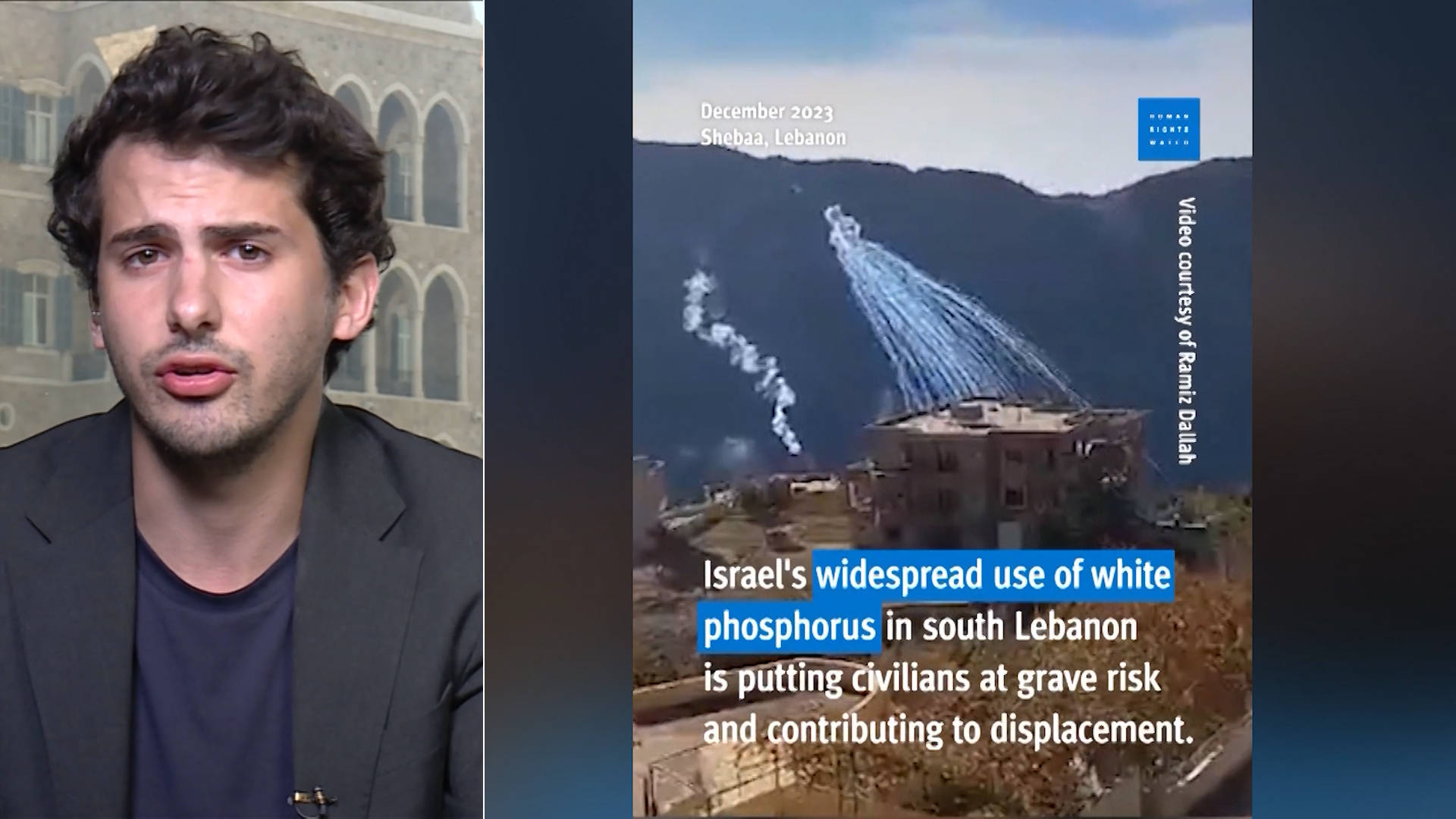

AMY GOODMAN: Israeli forces have illegally dropped white phosphorus munitions on densely populated residential areas in southern Lebanon, forcing many residents to flee. That’s according to a new report by Human Rights Watch documenting Israel’s use of the chemical in at least 17 municipalities across southern Lebanon since October, including five towns where the shells struck several residential buildings.

White phosphorus poses a high risk of excruciating burns and lifelong suffering, and its use as an incendiary weapon in civilian areas is a war crime, which, under U.S. law, should have implications for continuous military aid to Israel. The Intercept’s Ryan Grim questioned State Department spokesperson Matt Miller Thursday about the Human Rights Watch report.

RYAN GRIM: We’ve seen tons of reports now about the use of white phosphorus by the IDF, 17 municipalities across southern Lebanon since October, according to HRW. So, does the U.S. have any policy that it — with regard to the use of white phosphorus —

MATTHEW MILLER: So —

RYAN GRIM: — putting — setting aside whether or not these individual incidents occurred?

MATTHEW MILLER: Yeah, yeah. So, white phosphorus is something that’s commonly used in military operations to produce smoke, to obscure ground forces, mark locations or provide illumination. And just the usage by itself is not something that’s prohibited under international humanitarian law. But as with any type of military operation, civilians can’t be targeted. If white phosphorus is used, precautions have to be taken to minimize harm to civilians. And it’s incumbent on countries to use white phosphorus in ways that are consistent with international humanitarian law.

RYAN GRIM: Are these incidents concerning, that Human Rights Watch is saying that they were outside the bounds of what you just described?

MATTHEW MILLER: So, I’ve seen the reports, but that is the type of thing that we’d have to take a look at and assess before commenting in detail.

AMY GOODMAN: That was State Department spokesperson Matt Miller being questioned by The Intercept’s Ryan Grim.

After one Israeli attack on October 15th, at least two people from the village of Boustane had to be rushed to the hospital after inhaling white phosphorus smoke. Lebanon’s Ministry of Public Health says at least 173 people have been injured in the white phosphorus attacks, which have also caused hundreds of forest fires in Lebanon.

For more, we go to Beirut, where we’re joined by Ramzi Kaiss, a researcher in the Middle East and North Africa Division at Human Rights Watch investigating human rights abuses in Lebanon, lead author of the group’s new report called “Lebanon: Israel’s White Phosphorous Use Risks Civilian Harm.”

Welcome to Democracy Now!, Ramzi. Just lay out what you understand is happening in southern Lebanon right now when it comes to the use of — Israeli military use of white phosphorus.

RAMZI KAISS: Thank you, Amy. And thank you for having me.

As you noted, we released a report today documenting Israel’s widespread use of white phosphorus in south Lebanon. And what we found is that this widespread use is putting civilians at grave risk and also contributing to displacement.

As part of our research, our arms experts and digital investigations team reviewed over a hundred photos and videos and identified the use of white phosphorus munitions in 47 of them, and, when possible, we geolocated or precisely identified where those munitions had fell. In total, we found that white phosphorus was used in at least 17 municipalities stretching from southwest Lebanon near the Mediterranean all the way to the southeast near the occupied Golan Heights. And in five of those municipalities, we identified the use of white phosphorus munitions over populated residential areas.

As part of the research, we spoke to eight residents from the south, including the mayors of three of the towns where white phosphorus was unlawfully used. And what they told us was, you know, at the time of the attacks, many of these villages were still populated. There were people in them. In the case of al-Boustane, which you had mentioned, the mayor said that nearly all the village was still there, and when the attacks happened, two people were injured. In a separate town, in Kafr Kila, the mayor told us that, overall, between 20 to 25 people had been injured from white phosphorus use. And all the mayors that we spoke to had said that it, you know, turned the towns into a militarized zone and pushed people out of their villages. As you noted, the Ministry of Health had said that at least 173 people, as of May 28, have been injured as a result of exposure to white phosphorus. And we heard just about the fears that people have from its use in the south.

We think that the widespread use of white phosphorus in south Lebanon, you know, that there should be action taken. On the one hand, Israel should immediately prohibit the use of airburst white phosphorus munitions in populated areas because of the risk of indiscriminate attacks on civilians and the harm that we’re seeing being caused to civilians. Also, the widespread use shows that there’s a need for stronger international law on the use of white phosphorus. And I’m happy to speak more on that. And we also made a call to the Lebanese government to file a declaration with the International Criminal Court, giving it the jurisdiction to prosecute and investigate crimes committed within its jurisdiction since October 7. The government made a decision on this about a month ago, but then backtracked on it, unfortunately.

AMY GOODMAN: So, explain exactly international law when it comes to the use of white phosphorus, if you can go into that in more detail. And also, what about U.S. law?

RAMZI KAISS: Sure. Let me just start by saying that with white phosphorus, you know, it’s a chemical substance that’s dispersed in artillery fire, shells, bombs and rockets, and it has incendiary effects, as you had mentioned, that can cause death or lifelong suffering. It can set homes and agricultural areas and other civilian objects on fire, and, you know, continues burning until either it’s cut off from oxygen or the white phosphorus is depleted. So, when it comes to contact with people, it can burn down to the bone and cause lifelong suffering.

Now, it can also be used as a military tool, you know, to create smokescreens to obscure the movement of troops, or to mark or signal a certain area, but — and it also interferes with infrared systems and weapon-tracking systems. But under international humanitarian law, the use of airburst white phosphorus is unlawfully indiscriminate in populated areas and also does not meet the legal requirement to take all necessary precautions to avoid civilian harms. And these concerns are amplified, given the way in which we’re seeing white phosphorus used, particularly in south Lebanon and in Gaza, where it’s airburst over a certain area. And when that happens, the 116 felt wedges impregnated with white phosphorus can spread over an area of 125 meters to 250 meters, depending on the height and angle of burst, and indiscriminately cause harm to civilians and civilian objects in that area.

And so, with regards to international law, when it’s used as a weapon, white phosphorus is considered an incendiary weapon. And, now, incendiary weapons, they’re not explicitly banned under international humanitarian law, but customary international humanitarian law maintains that all parties to a conflict need to take all feasible precautions caused by these weapons. The only legally binding instrument with regards to incendiary weapon is Protocol III of the Convention on Conventional Weapons. Lebanon is a state party. Israel is not. But the Protocol III has two significant loopholes. On the one hand, it defines incendiary weapons as weapons that are primarily designed to set fires or cause burns, whereas — so, therefore, it excludes multipurpose munitions like white phosphorus. And also, it has much weaker language on the use of ground-launched incendiary weapons. So, what we’re seeing in Gaza and Lebanon, where it’s artillery-fired projectiles, they’re ground launched, and then they’re airburst over an area. And so, this is why we have long called for the closing of these loopholes and for stronger international law on the use of international — of incendiary weapons.

AMY GOODMAN: I wanted to go back to what Human Rights Watch confirmed in Gaza. In October, it reports that it had confirmed Israel using, firing white phosphorus munitions during attacks on Gaza, as well as along its border with Lebanon. Israel denied using white phosphorus, but previously had used the white phosphorus in attacks on the Gaza Strip, including in 2009. Israel’s military initially said —

RAMZI KAISS: That’s correct.

AMY GOODMAN: — it was currently not aware of the use of weapons containing white phosphorus in Gaza. Later, it said, quote, “The current accusation … regarding the use of white phosphorus in Gaza is unequivocally false.” Meanwhile, the new Human Rights Watch report on Lebanon also notes, “The Israeli military said that its main smoke shells do not contain white phosphorus, but stated that ‘similar to many Western armies, the IDF [Israel Defense Forces] also has smoke shells that contain white phosphorus … and the choice to use them is influenced by operational considerations and availability compared to alternatives.’” unquote. “The military further said that such munitions ‘are intended for smokescreens, and not for an attack or ignition,’” the report said. Can you explain all of this, Ramzi Kaiss?

RAMZI KAISS: Sure, sure. I’ll just start off by saying that, you know, Human Rights Watch documented the use of white phosphorus back in 2009 in Gaza, and then, subsequently, since October until today. We first documented it in October in south Lebanon and in Gaza. And then, subsequently, after that report, the Israeli military or the spokesperson denied, you know, the military using white phosphorus. But after that, several other rights groups, including Amnesty International, for example, documented the use of white phosphorus unlawfully in the southern Lebanese town of Tyre. Washington Post then did an investigation and found that the Israeli military used U.S. weapons in an attack that Amnesty said should be investigated as a war crime.

In response to this, the statement that you just mentioned came from the Israeli military, where they said that some of the smoke shells have white phosphorus, and they’re used to create smokescreens, and that, you know, their use of white phosphorus complies and goes beyond the requirements of international law. What our report, I think, shows is, in fact, that it’s being used unlawfully. It’s being used on residential populated areas, it’s causing harm to civilians, and it’s causing displacement in the south.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, I want to thank you very much for joining us from Beirut, Ramzi Kaiss, Human Rights Watch researcher investigating human rights abuses in Lebanon, lead author of the new report from HRW, “Lebanon: Israel’s White Phosphorous Use Risks Civilian Harm.”

This final description of the effects of white phosphorus from the Human Rights Watch report: “White phosphorus that contacts people can burn down to the bone. Fragments of white phosphorus can exacerbate wounds even after treatment and can enter the bloodstream and cause multiple organ failures. Already dressed wounds can reignite when dressings are removed and the wounds are reexposed to oxygen. Even relatively minor burns are often fatal. For survivors, extensive scarring tightens muscle tissue and creates physical disabilities. The trauma of the attack, the painful treatment that follows, and appearance-changing scars lead to psychological harm and social exclusion.”

Next up, deadly heat. As we enter this month, record scorching temperatures across the globe. We’ll speak with a climate scientist in Mexico, where howler monkeys are falling from the trees. We’ll also talk to a climate reporter about the heat wave scenario that keeps climate scientists up at night. Back in 20 seconds.

Post comments (0)