This is a rush transcript. Copy may not be in its final form.

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, “War, Peace and the Presidency.” I’m Amy Goodman.

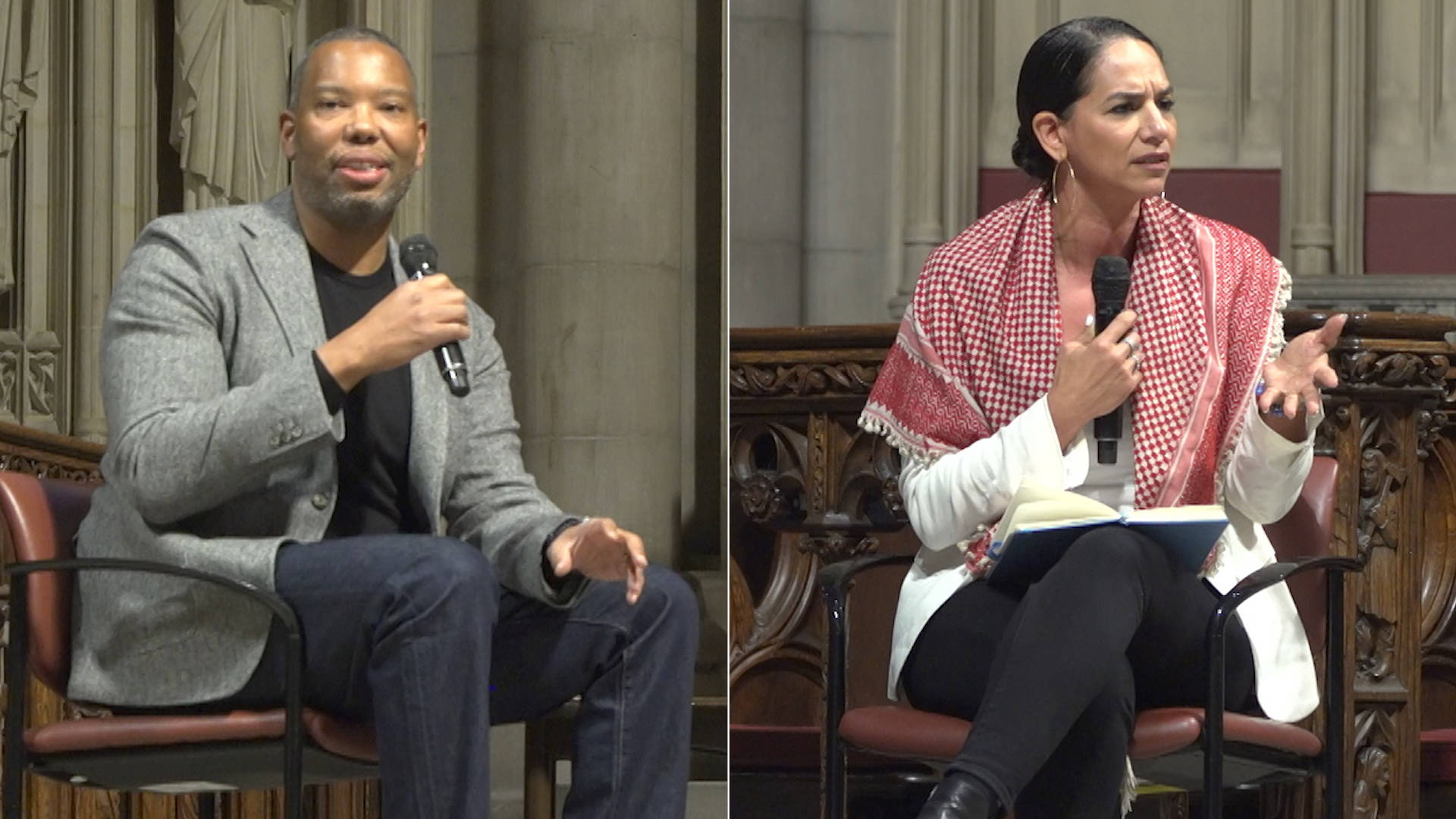

On Sunday here in New York City, more than 2,000 people packed the historic Riverside Church for a discussion about America and the war on Palestine. It was hosted by the Palestine Festival of Literature, or PalFest. The church, Riverside, where Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. gave his speech on April 4th, 1967, a year to the day before he was assassinated.

The event yesterday featured several speakers, including Palestinian human rights attorney Noura Erakat, a professor at Rutgers University, author of Justice for Some: Law and the Question of Palestine. Another of the panelists was Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor, professor of African American studies at Princeton University and contributing writer at The New Yorker magazine. You can see our interview with professor Yamahtta Taylor last week at democracynow.org.

In a minute, we’ll hear from human rights attorney Noura Erakat. She was introduced by the moderator and author Ta-Nehisi Coates. His new book, The Message, in part about a visit he took to the occupied West Bank and Israel that was organized by members of PalFest, the sponsors of yesterday’s event. This is what he had to say.

TA-NEHISI COATES: When I think about being here, I think about ancestors. And I think it would be wrong if I didn’t, if we didn’t proceed without acknowledging that. First of all, I was informed when I came here that this is where Edward Said’s funeral was. And so it’s incredibly appropriate to be here in this moment.

The second thing is something that Yasmin and I talked about and have been talking about for a year, even when we did the other event before, was the fact that this was also the place where Martin Luther King stood up against the Vietnam War and was so courageous. And I want to acknowledge that in his time, when he did that, a lot of people did not applaud. I want to acknowledge that there were many people who he thought of as his allies who left him.

NOURA ERAKAT: Sounds familiar.

TA-NEHISI COATES: Yes, yes, yes, yes. That’s why I think it’s very appropriate, right?

KEEANGA–YAMAHTTA TAYLOR: Absolutely.

TA-NEHISI COATES: Who urged him to be silent as bombs were being dropped on helpless people. And he did not do that. And so, I think, in that spirit, that’s the spirit in which we proceed in our conversation.

KEEANGA–YAMAHTTA TAYLOR: Yes.

TA-NEHISI COATES: We’re going to talk a lot about theory today, not that theory is irrelevant, but I do think it is important for us to ground ourselves in the reality of what is going on right now.

And, Noura, if you would just take a moment for us and speak to the ongoing genocide, the pain, the life lost, frankly, the role that we as Americans play in that? If you would just take a moment for us just to ground us so that we are not forgetting, so that we are not, you know, all the way up here?

NOURA ERAKAT: Thank you. Thank you, Ta-Nehisi. Thank you, Keeanga and to this audience again. Thank you for coming to find sanctuary collectively.

I think that this was a concern that after more than a year of watching slaughter of babies — this is essentially and continues to be a war on children in a besieged territory where 50% of the population is children, so even before a bomb is dropped, it is a war on children — that it’s really easy to then pivot to the theoretical piece to make sense of it. We want to make sense of it at this stage. And what gets lost is what’s happening.

And so, I appreciated — full transparency: Ta-Nehisi asked me to do this just, you know, right before this event. So I thought that the proper way to do it was actually to read testimony from the ground from a colleague, from a colleague who — who in Gaza, who is recounting, as of 6 a.m. this morning. One of his colleagues woke up to 32 members of his family who were killed in Jabaliya. And Jabaliya is in the north, which is now under now an even tighter siege and a campaign of extermination and ethnic cleansing. What he writes upon waking up at 6 a.m. and finding his family slaughtered is that, quote, “I live meters away from them. It is a matter of luck. I wish I died with them. Neither my heart or mind can tolerate this, my uncle, his wife and three sons and grandsons and daughters all deleted.” He also lost his brother earlier in the year.

And as we’ve been paying attention in this moment, which is important to ground, we’re on day 400 of genocide, but we’re on day 36 of the siege of the north. And the siege of the north is a tightening of the siege that already existed, right? And it’s a siege that even predates the beginning of this campaign, this genocidal campaign. It’s a siege that’s been in place since 2006 at the earliest, thinking about a land siege and a naval blockade. But 1993, if you go back to when Gaza is first circumscribed by barbed wire as a way to prepare for peace, the irony is that the preparation for peace was a program to isolate and separate the Gaza Strip from the rest of the question of Palestine and to call it the Palestinian statelet and never to leave the West Bank to negotiation, but it was done in the language of peace, that this doublespeak continues.

But now here we are, of this — and 36 days of this particular campaign. And we got the earliest indication of it on day six of this genocide, when there was an order to evacuate the north to below the Wadi Gaza line, right? The line which was the order, if you remember, when 1.1 million Palestinians — that’s more than half the population besieged — was ordered to leave the north to below the Wadi Gaza line. But note that that removal was a death sentence, as the World Health Organization called it a death sentence. How do you remove the immobile? How do you force the sick to travel? And those that did take the risk and travel were targeted on the humanitarian lines that they were given, indicating to us on day six that there would be no safe quarter, that this was a campaign of genocide. And it’s why Holocaust studies scholar Raz Segal, the very next day, published in Jewish Currents, “This is a textbook case of genocide,” right?

And it’s why 800 TWAIL scholars, Third World approaches to international law scholars — when people call me international law, you know, the constant question that I get is: How do you still believe in the law? And I’m like, I’m a TWAIL scholar. We never believed in it. We’ve been telling you it is a source and a site of oppression and colonial domination. My book tries to say that and tries to demonstrate how, despite this colonial structure, we can use it for emancipatory purposes, under which circumstances, right? Use it when it suits us. Abandon it when it doesn’t. Create new law when we can. It is a tool. It is not the word of God. It is not holy. It is subject to change and to change by us. So, those 800 TWAIL scholars who know that said, raising the alarm, this is genocide. This was all within the first week, all within the first week.

And now we’re hearing something known as the General’s Plan. The General’s Plan, which is the formula for exterminating the north, the 400,000 people total Palestinians left in the north, 100,000 particularly in the area now marked for ethnic cleansing. The General’s Plan is the brainchild of General Giora. What is his first name? Giora Eiland. Giora Eiland, who proposes this plan. Giora Eiland was also the architect of the Eiland Plan in the early 2000s, which competed with Ariel Sharon’s plan for unilateral withdrawal and disengagement, which was the withdrawal of Israeli settlers and the withdrawal of military installations, but the maintenance of occupation of Gaza. That Eiland Plan in the early 2000s was to ethnically cleanse all of Gaza into the Sinai, right? So, the idea that he’s now — and by the way, Mada Masr — so, thanks to, you know, our partners at Mada Masr — have written, wrote beautifully and thoroughly about the Eiland Plan.

But you have the 1993 circumscription of Gaza in preparation for peace. You have the Eiland Plan in the year 2000. You have the evacuation order on October 12th, which was called a death sentence. You have the calls that this is genocide since day seven. You have now the General’s Plan.

We have a year, over a year of bearing witness to what — you know, my job and other people’s job has been to illuminate what can’t be seen, what’s been obfuscated. They have illuminated it for us. At this point, it is not about us telling you what you have to read between the lines. It’s literally about what they don’t want to hear, not what is not being revealed, because they are telling us, they have shown us, it is evident, they are defending it. They call it self-defense, and they call the completion of the Nakba as the right to complete. So, it’s less obfuscation, right? And now it becomes more about it’s a battle of narrative: Who do you want to listen to?

AMY GOODMAN: Noura Erakat, professor at Rutgers University, author of Justice for Some: Law and the Question of Palestine, speaking Sunday here in New York at the historic Riverside Church at an event moderated by author Ta-Nehisi Coates. His new book, The Message. The event was hosted by the Palestine Festival of Literature. Also in that discussion, Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor, Princeton University professor. To see our interview with her, go to democracynow.org. The next PalFest event, Palestine Festival of Literature, will be in held London November 20th to mark the republication of Edward Said’s book The Question of Palestine, followed by events in Detroit, Philadelphia and Minneapolis.

When we come back, we’ll speak with Dutch Palestinian Middle East analyst Mouin Rabbani about Gaza, about Qatar suspending mediation talks between Israel and Hamas for a Gaza ceasefire, about Saudi Arabia hosting world leaders for an Arab-Islamic summit, and about protests in Amsterdam, where he is. Stay with us.

Post comments (0)