This is a rush transcript. Copy may not be in its final form.

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org. I’m Amy Goodman, with Juan González.

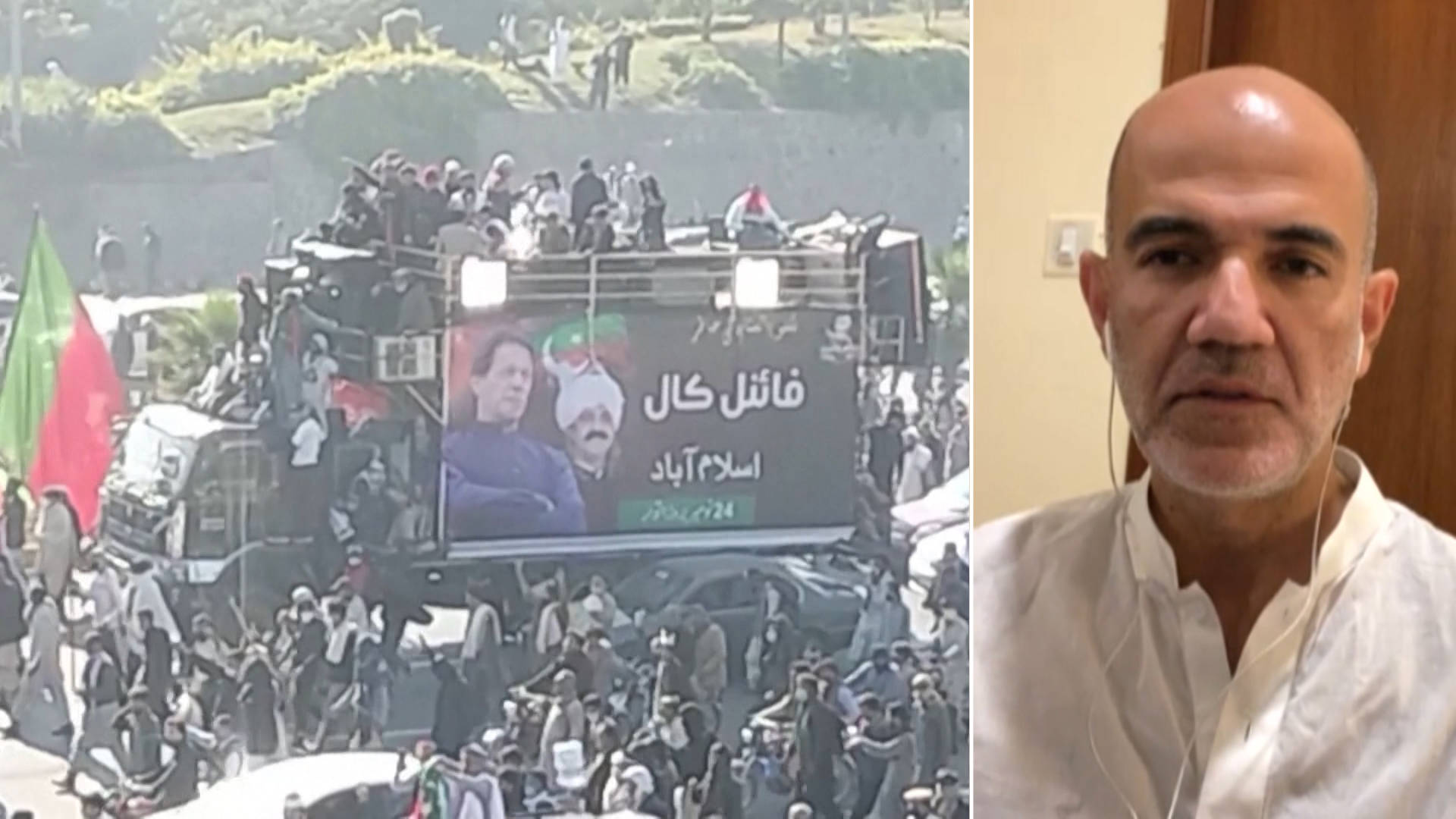

We end today’s show in Pakistan, where security forces in Islamabad arrested over a thousand protesters in a massive crackdown targeting supporters of jailed former Prime Minister Imran Khan during a march on the capital city. At least six people died in the protests that began Sunday. Khan’s supporters had vowed to stage a sit-in until he was released, but they ended the protest following the security crackdown, which has been described by Khan’s supporters as a “massacre.” Imran Khan has been in prison since August 2023 on what are widely viewed as politically motivated charges.

We’re joined right now by Aasim Sajjad Akhtar. He is associate professor of political economy at Quaid-i-Azam University in Islamabad. He’s also affiliated with Pakistan’s left-wing Awami Workers Party.

Thanks so much for being with us, Professor. If you can just start off by talking about what took place in the last few days? Now, Imran Khan’s supporters have called off the protest. But the mass protest that’s taken place and the number of arrests and deaths?

AASIM SAJJAD AKHTAR: Yes. Thanks, Amy.

Well, I mean, some of your viewers will know that this is a long-simmering conflict between the PTI, which is Imran Khan’s party, and the present government. It has many phases. The most recent sort of big sort of part of this sort of conflict was in February of ’24, when, in general elections, it’s widely sort of understood that Khan’s party won the majority of seats but, through various kinds of post-poll rigging, was denied an opportunity to run the government. And this was while Khan was in jail. And he’s been in jail now for, I think, 14 months.

So, this protest, which was called on the 24th of November, was yet another sort of big mass mobilization to demand his release, to demand the release of many other PTI leaders and supporters who have been in and out of prison both before and during this protest, and to basically say or to demand, in a sense, that this, what the PTI believes, and what I think is reasonable for it to believe, is an illegitimate government is called to account, and then sort of polls are held afresh.

And what transpired, as you noted, was a crackdown. Despite the crackdown, mind you, the PTI and its supporters managed to get into the city of Islamabad and all the way into what is called the D-Chowk, which is right close to a series of government buildings, including the Parliament. But then, late last night, they were pushed back after a lot of, well, initially, skirmishes, and then serious repression. And right now we don’t actually know the extent of how many people have lost their lives, how many people are injured, because a lot of that is being blanked out by the state media.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And, Professor Akhtar, to what do you attribute the mass popularity of Imran Khan? And also, this whole question that some of his supporters have raised, that he ran afoul of the United States when he was in office?

AASIM SAJJAD AKHTAR: Well, I mean, Imran Khan is, I think, a phenomenon that has many parallels around the world, sort of a self-proclaimed outsider who, I think, has built his popularity around the unpopularity of the so-called liberal centrist parties, or what we would call or I would call the liberal establishment, which have, over many, many decades now, acceded to, for instance, IMF conditionalities, have allowed the military, which, of course, is Pakistan’s most prominent and powerful political force, a free hand. And so, you know, all of these things. And there was a war on terror in Afghanistan and its effects in Pakistan. And Khan sort of pitched himself as an outsider, as an anti-establishment outsider, who wanted to change the system.

He came to power, as some of your viewers will know, and was in power for the best part of four years, between 2018 and 2022. And when he fell afoul of the military — initially, his coming to power was largely assisted by the military. But when he fell afoul of the military in 2022 is when he was booted out. But people like Imran, I think, in a sense, you know, are able to play to their gallery better when they’re out of power. And so, the last couple of years, anti-incumbency, whether it be because of inflation, unemployment — again, you know, a regime that is pandering to the military at every juncture, I think that has, in a sense, further inflated this support base that Khan enjoys, in a very youthful country, mind you. Pakistan’s median age is about 23.

And as far as the America thing goes, I don’t think there’s any conclusive evidence that there was sort of direct meddling in that particular decision for Khan to be booted out in April 2022. That was largely because he fell afoul of the military. But again, as your viewers will know, this is not a country in which the United States needs to intervene at any one juncture. It’s had a larger-than-life role, partly in sponsoring and propping up Pakistan’s military, since the Cold War. So, the fact that, you know, Khan touches a nerve by speaking about American involvement, I think, also speaks to how you can take a particular grain of truth and sort of combine it with mass anti-incumbency to generate a great deal of resentment.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And you mentioned the Pakistani military. Could you talk about the outsize role of the military within Pakistani society? And are there long-established ties between it and the U.S. military?

AASIM SAJJAD AKHTAR: That’s right, yes. As I said, this is a story that goes all the way back to the Cold War. Pakistan was widely viewed by the Washington as a anti-communist frontline state through the 1950s, ’60s, and then, most notoriously, after 1977, when the so-called jihad was backed by America and sort of, in a sense, operationalized by the Pakistani military. And then, again, when that story turned on its head, and the old jihadis were now cast as terrorists after 2001, again, it was a military dictatorship of Pervez Musharraf, which was backed heavily by the Bush administrations, and even later on by the Obama administration. So, there’s a long story, and the Pakistani military has benefited from American support to not only dominate Pakistan’s political life, but also largely dominate its economy.

And I think what has happened with Khan — because, as I noted earlier, Khan actually initially came to power with the support of the military. But what has happened is that this long, sort of gestating, simmering sort of undercurrent of sentiment amongst ordinary people about the outsized, as you said, role of military in Pakistan’s political, economic and social life, I think it is coming to a head somewhat. Now, time will tell, however, whether Khan and his party are really able and willing to take on the military and sort of the militarized political economy, so as I would say, rather than perhaps just seeking a route back into power. But that doesn’t excuse, of course, the fact that they have been subject to serious repression over the last couple years. And I think that has simply reinforced Khan’s massive popularity.

AMY GOODMAN: So, do you see parallels between Imran Khan, who can, you know, as you say, mobilize massive number of people, from prison, into the streets, even as so many are arrested and a number killed — do you see parallels between him, who faces a number of corruption charges, and President Trump?

AASIM SAJJAD AKHTAR: Yeah, as I noted earlier, I mean, he is — as I said, Imran, I think, is sort of, in a sense, a symbol of the type of political leader that has emerged, I think, over the last 15, 20 years. Trump is another example. Right next door to us, in India, is Modi. I mean, there’s many such examples, sort of this so-called new outsider, who perhaps really isn’t as much of an outsider as the narrative would suggest, that builds upon, as I said, the resentment, the disillusionment of the liberal — of people with established parties and with the establishment at large.

And certainly, there’s parallels. In fact, Trump and Imran, when they were both, in their earlier incarnations, in office in 2019, sort of had this very buddy-buddy-type engagement when they met. And right now, right after your election on November 5th, there was a lot of PTI online sort of media — mind you, a lot of the PTI has a great deal of support in the diaspora — that played up this notion that maybe a Trump administration would coax the Pakistani military into getting Imran out of power. So, there is a lot of parallels. They’re not the same thing. They can’t be reduced to the same thing. But I do think that it tells us a lot about how the liberal center continues to fail and pave the way for these so-called outsiders to thrive.

AMY GOODMAN: Aasim Sajjad Akhtar, we thank you so much for being with us, associate professor of political economy at Quaid-i-Azam University in Islamabad.

That does it for our show. Tune in Thursday, Thanksgiving, for a special broadcast with Indigenous scholar Nick Estes and Ta-Nehisi Coates, author of The Message. And on Friday, we’ll speak to Nemonte Nenquimo, an Indigenous leader from the Amazon in Ecuador, as well as Palestinian poet Mosab Abu Toha from Gaza.

That does it for our show. Special thanks to Mike Burke, Renée Feltz, Deena Guzder, Messiah Rhodes, Nermeen Shaikh, María Taracena, Tami Woronoff, Charina Nadura, Sam Alcoff, Tey-Marie Astudillo. I’m Amy Goodman, with Juan González. Happy holidays!

Post comments (0)