This is a rush transcript. Copy may not be in its final form.

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman, as we continue our coverage of Israel’s war on Gaza. The World Health Organization Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus warned Thursday the future of an entire generation of Palestinians is in serious peril.

TEDROS ADHANOM GHEBREYESUS: On Tuesday, the Integrated Food Security Phase Classification partnership said that Gaza faces imminent famine, because so little food has been allowed in. Up to 16% of children under 5 in northern Gaza are now malnourished, compared with less than 1% before the conflict began. Virtually all households are already skipping meals every day, and adults are reducing their meals so children can eat. Children are dying from the combined effects of malnutrition and disease and lack of adequate water and sanitation. The future of an entire generation is in serious peril.

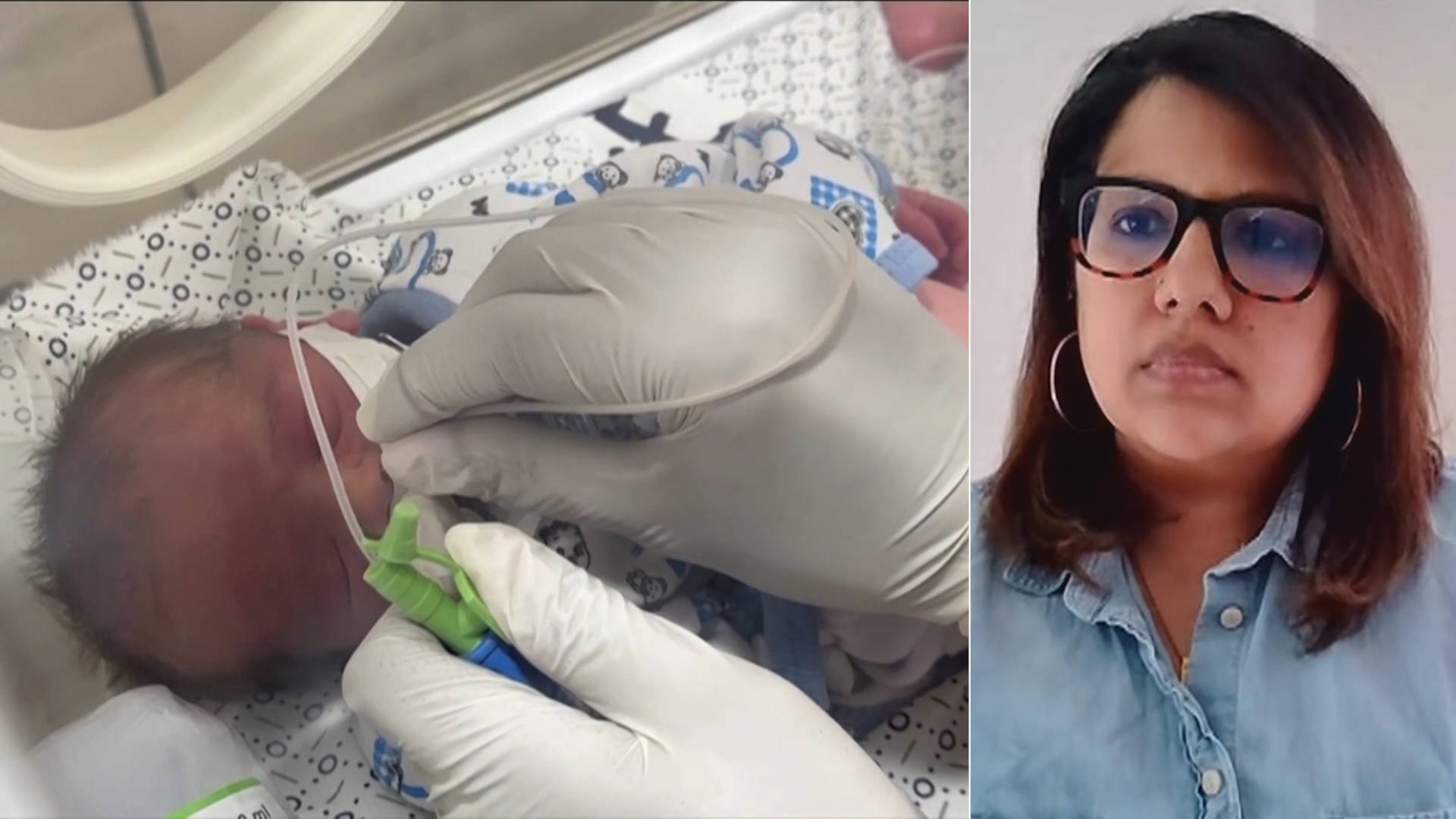

AMY GOODMAN: We’re joined now by Dr. Nahreen Ahmed. She’s a pulmonary and critical care doctor based in Philadelphia, the medical director of the medical humanitarian aid group MedGlobal. Her first medical mission to Gaza was January. Earlier this month, she returned to Gaza, where she volunteered for two weeks. She left on Wednesday and is joining us now from Gaziantep, Turkey.

Dr. Ahmed, thanks so much for being with us as you’ve just come out of Gaza. Talk about what you’ve seen in terms of child hunger.

DR. NAHREEN AHMED: Yeah. Thank you for having me and for this opportunity to speak about what’s going on.

This was, as you mentioned, my second trip back, and it was pretty clear how rapidly the malnutrition has risen in Gaza. I had the ability to actually go and see what was happening in the north, as well. I’ll start with what’s happening in the south.

MedGlobal has a stabilization center that’s in the south of Gaza that is purely to treat malnutrition. So, the situation is so bad that there needs to be specific centers that are primarily treating patients with malnutrition. As was mentioned before in the broadcast, the most vulnerable population here are children under 5. But we are also seeing that pregnant and lactating women are suffering from this, as well, and there’s a rapid increase in malnutrition across mothers, as well. You can imagine that these two things are connected, as children under 5 or newborn babies are receiving nutrition from their parents, from their mother. And with the fact that mothers are also experiencing malnutrition, we’re seeing that newborn babies are being born at an astoundingly low weight. Infections are happening very rapidly at these young ages as a consequence. And again, mothers are going through the mental health crisis of experiencing the inability to feed their children because of their own level of malnutrition.

The percentages of malnutrition from when I went in January to when I just returned now have doubled. That’s in practically a month’s time. And as was already mentioned, this situation is happening so rapidly that even if aid was increased tomorrow, we would still be in a severe situation where the amount of food would just not be enough in the immediate term. And so, this is what I, unfortunately, witnessed with my own eyes.

AMY GOODMAN: And can you talk about what it means when children in incubators, when a little older children experience malnutrition, how they are able to cope, if they get some kind of aid, they go out of the hospital, being more vulnerable, and especially in the, to say the least, extremely harsh conditions now of Gaza?

DR. NAHREEN AHMED: Yeah. So, I mean, you know, thinking about this, first of all, this is not just a problem that’s solved by the nutrition therapeutic feedings that we’re giving. This is a cyclical problem that, first of all, one, it’s very painful. A child suffering from hunger, this is an extremely painful thing to experience.

Two, the access to food once somebody is released from an inpatient unit is still going to be a problem. We see children chasing after trucks where food distribution is happening. We see children chasing with water bottles to the water distribution trucks. I mean, this is a situation that is also degrading for them, to have to experience finding food and water in this way.

Lastly, you know, when we talk about vulnerability, we’re talking about vulnerability to infections. This is what we’re seeing the most in a hospital in the north of Gaza, where almost every single patient that I saw in the inpatient pediatrics unit was suffering from malnutrition. Each of these children had an infectious complication. Either they were suffering from liver disease from rampant hepatitis A from lack of access to clean water, or they had severe pneumonias that they were even more vulnerable to complications of because of the level of malnutrition, or, you know, diarrheal diseases that were happening for the same reasons. And so, children are dying from infectious processes, as well, the complications of having severe malnutrition. All of these issues are preventable. All of these issues are preventable.

AMY GOODMAN: I want to turn to Hala Ashraf Deeb, a Palestinian who has nothing to feed her children.

HALA ASHRAF DEEB: [translated] What has this child done to suffer from hunger? I cannot find milk for five shekels or a packet of milk from the agency. There, the normal milk is for 150. There is no work. There is no food, no drinks. We are eating plants. We started eating pigeon food, donkey food. We are like animals.

AMY GOODMAN: That is a Palestinian mother in Gaza. The U.N. agency for Palestinian refugees, UNRWA, is calling the situation in northern Gaza beyond desperate. Maybe that’s why the Israeli government wants them to be — to lose all their funding, the most comprehensive agency for Palestinians there in Gaza. In a post on X, UNRWA said its staff visited Kamal Adwan Hospital, and “fuel and medical supplies were delivered, but aid is just a trickle. Food needs to reach the north now to avert famine,” UNRWA said. You went to that hospital. Can you describe also the difference between January and now? And what about the doctors and the medical staff? How are they dealing with all of this?

I think we just lost Dr. Nahreen Ahmed, so we’re going to go to a break and see if we can get her back. Dr. Nahreen Ahmed is a pulmonary and critical care doctor based in Philadelphia, medical director of the medical humanitarian aid group MedGlobal. She just got out of Gaza and is speaking to us from Gaziantep, Turkey. Back in a minute.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: Nina Simone singing “Mississippi Goddam.” In a moment, we’re going to go to Mississippi, where a so-called Goon Squad, self-described, of police officers and sheriff’s deputies have just been sentenced to years in prison for torturing their victims. But we’re going to see if we can now resume our contact with the doctor just out of Gaza. But first, we’re going to keep looking at the looming famine there. This is Amber Alayyan with Médecins Sans Frontières — that’s Doctors Without Borders — speaking at the United Nations on Tuesday.

DR. AMBER ALAYYAN: The hospitals rely on quota systems for how many drugs they keep in their pharmacies, in their stocks in each department. And they have to choose between whether do I fully stock my operating theater, my ICU or my emergency room. And this is where you have doctors faced with horrific decisions of having to intubate and amputate children and adults without anesthetics in emergency rooms.

Part of the reason for this is the lack of medications or the lack of medications accessible at that time. Part of the reason is that we have internally displaced people living in hospitals, sheltering in hospitals, because they have nowhere safe to go. And what that means is they are staying in hospital beds. So, what does that mean for injured people? They arrive, they get a quick and dirty surgery in an emergency room or in an operating theater, and they have nowhere to be hospitalized afterward, or when they are, they are lost all throughout the hospital, and our teams spend all day searching for the patient that they just operated on 12 hours before.

What does this mean over the long run? The longer this war goes on, the longer these wounds have to rot. And I mean really rot. The infections are getting worse and worse, and it’s horrific. It’s horrific for our providers, and it’s absolutely horrific for these patients.

AMY GOODMAN: Dr. Amber Alayyan is with Doctors Without Borders. She went on to describe how the humanitarian crisis in Gaza is impacting women and children.

DR. AMBER ALAYYAN: Two populations are particularly vulnerable. Pregnant and lactating women, who were already facing iron deficiency anemia before the war, which puts them at risk for hemorrhage during birth, with the war, it puts them in a state of undernourishment or malnutrition, potentially malnutrition, which means that they can’t breastfeed their children properly. The milk doesn’t necessarily come in, and it’s definitely not enough. And the other population is children under 2 years, which is the breastfeeding age.

There’s not enough space for us to work closely with the mothers to help them start lactating again. We can’t even access them. And to be able to do that, you have to have day-to-day activities with those women, and that is not something that’s possible for us right now. Those children need to be breastfed. If they can’t be breastfed, they need formula. To have formula, you need clean water. None of these things are possible. What we’re talking about is women who are squeezing fruits, dates into handkerchiefs, into tissues, and feeding — drip-feeding their children with some sort of sugary substance to nourish them.

AMY GOODMAN: Dr. Amber Alayyan of Médecins Sans Frontières, Doctors Without Borders, speaking at the United Nations on Tuesday. We’re rejoined with Dr. Nahreen Ahmed, pulmonary and critical care doctor based in Philadelphia, just out of Gaza on Wednesday. She’s speaking to us from Gaziantep, Turkey. If you could go on to talk about, Dr. Ahmed, the mental health situation of the people in Gaza, particularly children?

DR. NAHREEN AHMED: Yeah. The mental health situation is devastating. Prewar, 50% of Gazan children were experiencing some PTSD from prior conflicts. It’s important for us to remember that this is not the first time that they’ve experienced this kind of trauma. Given that 50% of children were experiencing that, we’re up to probably 100%, presumably, of children who are experiencing trauma based on the day-to-day proximity to missile strikes and experiencing what they’re experiencing.

Our team that went with me this last week, in a collaboration with an organization called MeWe International, we actually went to several of our medical access points in shelters across Rafah, and we spoke to women and children about what they’re experiencing, and initiated a community-based approach towards providing mental health support. And this was using things like music, activity, very low cost because it’s so hard to get supplies or — you know, when it comes to mental health, we’re not just talking about medications. We’re talking about the ability to give agency and a voice and empowerment back to people.

And what we heard was the amount of children just unable to dream. That’s what’s the first thing they tell us, that “We have no dreams. We used to have dreams. We have no dreams. We cannot imagine that our lives will ever go back to normal.” We’ve heard children say, “I just want to go home. I want to be back in the safety of my home.” In an exercise that we did with a group of women and children — and this was mothers and their children, caregivers and their children — the number one thing, when asked for people to think — for them to think about a positive — something positive that they could hold onto, they would draw a picture of them returning to their home. This was overwhelmingly the number one thing. And most of these children have been displaced more than one time. And they just talk about how much they miss their home, how much they miss playtime activities, playing with children, going to school. We met so many children and adolescents who just wanted to be back in school. They’re missing that opportunity to have any kind of intellectual stimulation, and it’s causing a great deal of depression, anxiety, and just absolute a horrific experience for all involved.

AMY GOODMAN: Dr. Ahmed, we thank you so much for being with us. Dr. Nahreen Ahmed is a pulmonary and critical care doctor based in Philadelphia with the group MedGlobal. She’s medical director of the medical humanitarian aid group. Her first medical mission to Gaza was January. She just left Gaza on Wednesday, speaking to us from Gaziantep, Turkey.

Post comments (0)