This is a rush transcript. Copy may not be in its final form.

AMY GOODMAN: “Indonesia, the scene of two of the 20th century’s epic slaughters, may be on the verge of a return to army rule at the hands of its most notorious general.

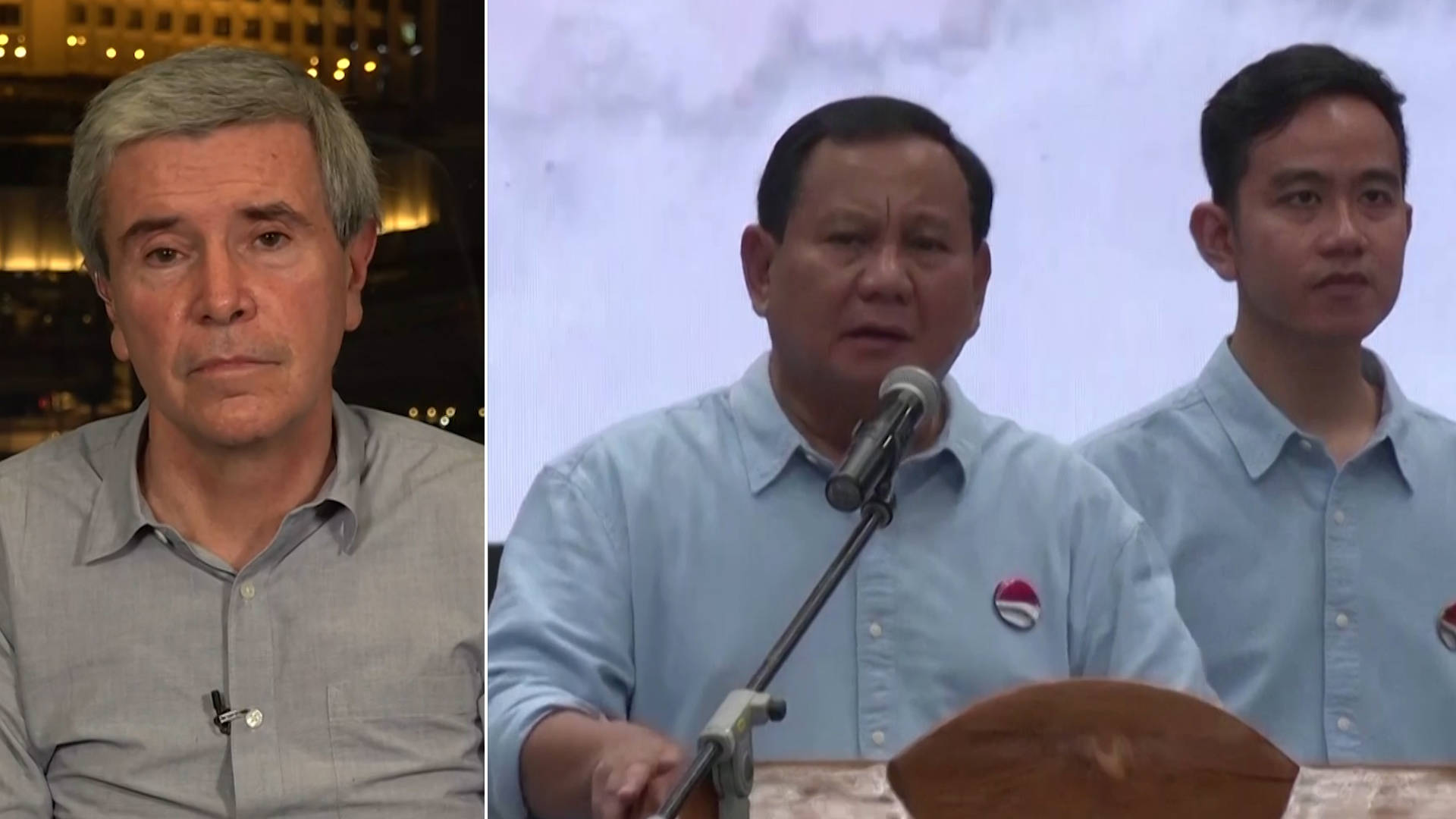

“Gen. Prabowo Subianto, a longtime U.S. protégé implicated in the country’s massacres, once mused about becoming ‘a fascist dictator’ and is now a serious threat to assume the presidency.”

Those are the opening two paragraphs of a new article in The Intercept by the award-winning journalist Allan Nairn, who’s spent decades covering Indonesia and the country it occupied for a quarter of a century, East Timor. Allan is joining us now from Jakarta, the capital of Indonesia, ahead of Wednesday’s election in Indonesia.

Welcome back to Democracy Now!, Allan. Why don’t you start off by just laying out the scene, what’s about to happen tomorrow and who exactly Prabowo is?

ALLAN NAIRN: Well, General Prabowo is the most notorious massacre general in Indonesia, and he’s also the general who was closest to the U.S. as he was carrying out his mass killings, abductions of activists and systematic tortures. He was also the son-in-law of the former dictator of Indonesia, General Suharto. Prabowo described himself to me as “the Americans’ fair-haired boy.” He mused about becoming “a fascist dictator.” He told me, “Indonesia is not ready for democracy.”

And he described in detail how he received training from the U.S. at Fort Benning and Fort Bragg, how when, in 1998, Suharto was falling, and he, Prabowo, was in the process of kidnapping activists, he was in regular consultation with the U.S. Defense Intelligence Agency. In fact, Prabowo told me that he reported to the USDIA at least once a week. He also described how, under a Pentagon program known as JCET, Joint Combined Exchange and Training, he, General Prabowo, brought fully armed troops into Indonesia on at least 41 occasions. And Pentagon documents back up Prabowo’s account. According to the general and those Pentagon documents, while the U.S. troops were in Indonesia, after, as the Pentagon put it, Prabowo opened the door to them, they started doing reconnaissance and making plans, contingency plans, for a possible future U.S. invasion of Indonesia — as Prabowo put it to me, for “the invasion contingency.” So, these armed U.S. troops, which Prabowo brought into Java and Sumatra and other places in Indonesia, were laying the groundwork for a future U.S. invasion, if the U.S. chose to do that. This is particularly interesting since Prabowo styles himself, as he’s running for president now, as a nationalist. And he attacks anyone who opposes him as an antek asing, a foreign lackey, when in fact he is the one who was closest to the U.S., who was helping the U.S. plan for an invasion, and who in more recent years helped to kill a workers’ rights lawsuit against Freeport-McMoRan, the American mining giant, which is stripping the hills and forests of de facto occupied West Papua.

And he is the general, most importantly, who led many of the massacres in East Timor after the Indonesian Army invaded with the green light from President Gerald Ford and Henry Kissinger. In one case, in the village of Kraras, Prabowo and his forces killed hundreds of fleeing civilians. He later was involved in other massacres and directing assassinations of political activists in Aceh and West Papua.

And now he may be on the verge of assuming the presidency. He’s tried for many years to seize power. He’s tried multiple coup attempts. But this time he has the backing of the incumbent government, the incumbent civilian President Joko Widodo, Jokowi, and the state apparatus is being put behind General Prabowo. The Army and police are going out and intimidating poor people at the neighborhood level, telling them that if they don’t vote for Prabowo, the authorities will know about it, and they’ll be in trouble. People are being threatened with having their — poor people are being threatened with having their government rations of rice and cooking oil cut off if they don’t vote for Prabowo. Academics who recently spoke out against this use of state power to push this general into office are now being visited and intimidated by the police. And last Wednesday, there was a meeting that included Army generals and intelligence officials, where they discussed a plan to, if necessary, do voter fraud to push General Prabowo over the 50% threshold he will need in order to win in tomorrow’s election. It’s a three-candidate election. And if he gets over the 50% threshold and gets a sufficient number of votes in the provinces outside Java, he will automatically become the president-elect. And the plan that was discussed at that meeting among those senior military and intelligence officials was that there was an existing plan to do fraud, if necessary, to push the general over that threshold and impose him on Indonesia as their new president, really their new ruler.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Allan, Allan, I wanted to ask you — you mentioned that the incumbent president, Joko Widodo, is backing Prabowo. How do you explain this change, since he defeated the general in two previous elections and once —

ALLAN NAIRN: Yes.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: — talked about actually holding him on trial for war crimes?

ALLAN NAIRN: Right. It’s a very important question, and it has a lot of Indonesians outraged. When Jokowi defeated Prabowo the first time around in 2014, he, the incumbent president, the civilian, Jokowi, had the support of many massacre survivors and human rights activists. And they did — internally, the Jokowi government did talk about putting General Prabowo and other generals, like General Wiranto and General Hendropriyono, on trial for war crimes. I have been publicly calling for that for years and also calling for their U.S. sponsors to be tried for war crimes. And, in fact, in the early years of the Jokowi administration, I met with some of his advisers in the palace and discussed this with them. And what they kept saying was, “Yes, yes, but it will take time. This is very dangerous. We have to go slowly.” But they said that that was the direction they were moving in. However, they never got there. They never even attempted to stage the trials.

And then, in 2019, after Jokowi defeated General Prabowo for the second time, Prabowo staged the latest of his many coup attempts by backing street riots that involved mass looting and burning in Jakarta. And it was at that point that President Jokowi said, “Enough.” He couldn’t take it anymore. And according to intermediaries from both sides, from both the Prabowo and the Jokowi side, Jokowi then decided to bring Prabowo into the tent, in the hope that if he did that, if he brought him inside the government, that would put an end to the coup threats and the incited street riots. And, in fact, it did. He brought Prabowo in. He made him minister of defense. And the two then grew close. Their interests coincided. Jokowi, the president, became increasingly wealthy. Prabowo backed the Indonesian military policy of killing civilians in de facto occupied West Papua, where there is strong sentiment for independence.

And this time around, when this next round of elections was coming up, the incumbent civilian president, Jokowi, decided he wanted to try to extend his own term, even though there’s a two-term limit, as in the United States. He looked into options for maybe getting a third term or maybe postponing the elections, but he wasn’t able to pull those off. So he made a deal with General Prabowo, with this massacre general, who is responsible for the slaughter of thousands and thousands of civilians across Indonesia and in occupied East Timor. President Jokowi made a deal to back him and use the state apparatus to help install him as president, and Jokowi lent his own son, Gibran, to General Prabowo as his vice-presidential running mate. And he did that even though the son of the president is too young to be vice president under Indonesian law. There’s an age limit. He’s only 36. You have to be a minimum age of 40. But he strong-armed that through the Supreme Court, where the president’s brother-in-law was the chief justice. He strong-armed it through the electoral commission. Official state bodies have already ruled that those two actions were unethical, but it doesn’t matter. The current ticket is General Prabowo, the massacre general, and Gibran, the president’s underage son.

And the whole state apparatus is being mobilized, on the one hand, to intimidate and threaten the poor with trouble and the cutoff of their food and their cooking oil if they don’t vote for Prabowo, and, on the other hand, mounting a very sophisticated, very disgusting public relations campaign, which portrays this notorious general as a gemoy, a fat, adorable cartoon character who, in videos and in ads, can be seen dancing. And to people who are not familiar with the history of the massacres, two of the worst slaughters of the 20th century, the U.S.-backed massacre, when the Army first seized power in ’65, of anywhere from 400,000 to a million civilians, and then the murder of a third of the population by the invading Indonesian Army in Timor with U.S. weapons and backing, and not familiar with Prabowo’s role in that slaughter in Timor and elsewhere, to those people — because, you know, these matters are not discussed in the schools or in the state media — the ads have some impact. And that, combined with the intimidation, makes him a strong threat to take power in the election.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Well, Allan, specifically, you mentioned how Prabowo has sought to rebrand himself. But what of the youth of Indonesia, who now make up 52% of the electorate, those under 40 — how have they been suckered into this narrative?

ALLAN NAIRN: I don’t hear anything.

AMY GOODMAN: We’re going to have to go to a break, Juan, because it looks like the IFB dropped for Allan. We’re going to then come back to speak with him, Allan Nairn, longtime investigative journalist, who’s been covering Indonesia for decades. He’s speaking to us from Jakarta, Indonesia. He’s written a piece in The Intercept headlined “Indonesia State Apparatus Is Preparing to Throw Election to a Notorious Massacre General.” We’ll be back with him in a minute.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: The group Helado Negro. They signed on to Artists for Ceasefire. This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman, with Juan González, as we continue our conversation with longtime investigative journalist Allan Nairn, who has covered Indonesia and Indonesian-occupied East Timor for decades. His piece in The Intercept, “Indonesia State Apparatus Is Preparing to Throw Election to a Notorious Massacre General.” Juan?

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Yes, Allan, before we lost you, I was asking you — you had mentioned Prabowo’s attempts to rebrand himself. And I asked about the young voters of Indonesia, who make up about 52% of the electorate. How have they bought into this narrative? And also, what does it say about democratic elections that a general with this kind of a record is likely to be victorious in an election?

ALLAN NAIRN: Well, we don’t yet know if he’s likely, but he has — he’s a strong threat to win, because the muscle of the state apparatus is behind him. Part of the reason there — they, to some extent, can get away with that, because textbooks and the press are not honest about how the Army originally came to power, with the U.S.-backed slaughter in 1965 of anywhere to — of 400,000 to a million civilians, and then the invasion of East Timor, with a U.S. green light in weapons, where they killed a third of the population, which was the most intensive proportional slaughter since the Nazis. And they’re definitely not familiar with General Prabowo’s role in Timor and in the Aceh assassinations and in terrorizing civilian population in West Papua.

And it’s a two-pronged approach that they’re using, basically pressuring and coercing the poor with threats to their well-being, because many poor people know they live at the mercy of what’s called the apparat, the Army and the police, and threats to their food, and then, for the middle and upper classes, and especially the young people, this PR campaign that portrays the general as a cuddly cartoon character. And none of it would be possible without the backing of the incumbent civilian president, who basically bowed to Prabowo and the Army after Prabowo’s 2019 ultimate coup attempt. So, by violence, Prabowo brought himself inside the government. And now that government is preparing to attempt, if necessary, through fraud, to install him and give him the ultimate power. And he’s talking about modifying the way the presidency works, returning to an older draft of the state constitution, which could make him a virtual dictator if he wants to be.

AMY GOODMAN: Allan, before we wrap up, a couple quick questions. Prabowo is the former son-in-law of the longtime authoritarian leader Suharto, responsible for Indonesia invading East Timor. You and I survived the 1991 massacre there, where Indonesian soldiers, armed, trained and financed by the United States, opened fire on defenseless Timorese, killing more than 270 of them. They beat you up, fracturing your skull. Talk about how Prabowo’s involvement in Timor, killings in Indonesia, as well, and then his supporting of coups led him to where he is today — I was amazed that he was willing to grant you an interview years ago, where he talked about becoming a fascist dictator — and where he stands, on everything from ISIS to what’s happening today in Gaza. After all, Indonesia has the largest Muslim population in the world.

ALLAN NAIRN: Yes. Well, I met with him twice in 2001. And I actually was meeting with him because I was investigating two particular murders of civilians, and I wanted to find out what he knew about them. And I think, possibly, he enjoyed speaking to an adversary.

But regarding the Santa Cruz massacre in Timor that we survived, Prabowo said to me, “That was an imbecilic operation.” And he objected to it, not because of the hundreds of Timorese the Army slaughtered, but because they did it in front of us. And because they did it in front of us and we survived and were able to report it to the outside world, and other foreign witnesses, like Max Stahl, were able to do the same, that we were able to get the U.S. Congress to, over time, through grassroots action in the United States, cut off for a while the U.S. arms supply to Suharto, which helped to lead to Suharto’s downfall, according to Suharto’s former security chief, Admiral Sudomo. So, [Prabowo] said, “That was imbecilic. You don’t” — he said, “You don’t do it in front of outside witnesses. You do a massacre in an isolated rural village where no one will ever know about it.”

And Prabowo was able to stage his series of coup attempts over the years, in part because he was — he had the support of the Indonesian Army, which was, in turn, backed by the United States. He, in particular, was the Americans’ favorite. He described himself as “the Americans’ fair-haired boy.” And he had the support of the Indonesian oligarchy, as well. And he certainly has their backing in this election.

And with regard to Israel, Prabowo, after he became defense minister, made a special effort to draw Indonesia closer to Israel. The two countries do not have diplomatic relations. The Indonesian population now is outraged by the slaughter, the genocide that Israel is conducting in Gaza. But Prabowo was attempting to bring Israel closer to Indonesia. There was already a covert relationship with Israeli intelligence and with the Israeli military, where intelligence equipment and training was given. And Prabowo started working with Trump, and later Biden, to attempt to bring the two countries together, similar to what other predominantly Muslim countries did under the Abraham Accords. Prabowo met with a senior Israeli security adviser. When this came out, he was forced to retreat from this policy. And at this moment, the Indonesian government and Prabowo are posing as if they oppose what Israel is doing. But if he becomes president, there’s a very good chance that those relations will grow even closer and perhaps be formalized.

AMY GOODMAN: Allan, finally, the former Supreme Court chief justice, retired now, tweeted out that you should be captured, as you give out this information. Are you concerned about your own safety? I think we just lost our connection to Allan. Allan Nairn, longtime investigative journalist, has been covering Indonesia and occupied East Timor for decades. East Timor has since become an independent nation. We’ll link to his new piece in The Intercept, “Indonesia State Apparatus Is Preparing to Throw Election to a Notorious Massacre General.” The election is Wednesday, February 14th.

Post comments (0)